This is a writeup of how we went about making Camparc, a panoramic camera ball.

The story starts in July 2014 when STRP asks us to make a public space game for a ‘scene’ — one of the events leading up to their 2015 biennial. They were looking for something eye-catching, accessible to a broad audience, fun for both participants and spectators, and of course it would need to be about tech in some way. The game would be played in the Strijp‑S area of Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

We cycled through a number of concepts together. An early idea was focused on doing things with large balls and maybe tracking them with cameras. A later concept was titled ‘Selfietopia’ and proposed a playground filled with camera toys for making selfies with.

Ingredients from those earlier concepts came together in Camparc: camera toys such as Panono and Bubl. New ways of seeing such as goal-line technology. The pleasure of playing with a huge ball in both Katamari Damacy and the earth ball games of the New Games movement.

It was our hope Camparc would let people playfully explore new ways of technologically augmented seeing, and that it would give people a tool with which to explore the Strijp‑S area in new ways.

Many different things had to come together in the final experience. For example, getting a video stream from the balls to show up on an LED trailer turned out to be non-trivial. But here I will talk about the design of the hardware and I will also go into how we created anamorphic puzzles for people to play with.

The Gilliam-Dyson Direction

So the starting point was to do something with big balls. We went on a hunt for a good base and eventually settled on water balls. They are large, transparent and afford opening and closing. Perfect for our purposes.

The notion of transparency and seeing the tech inside of the ball lead to a direction for the visual language which was equal parts Terry Gilliam sci-fi prop and James Dyson vacuum cleaner.

We worked with Aldo Hoeben on this project. He was responsible for the design and development of the balls as well as the software behind them. The cool thing about working with Aldo was that he has a background in industrial design, has an artistic practice focused on projection mapping and panoramic photography and is a 3D printing enthusiast to boot. In other words, his unique set of skills was a perfect match for the challenges of this project.

It was Aldo who starting from my Gilliam-Dyson direction created the brightly coloured custom 3D-printed parts which give Camparc its constructivist look. It is an aspect of the project I am still very proud of. More than once during a conversation with a player about ‘how it works’ was I able to simply point to every single component and talk them through it.

Another neat aspect of the balls is that all the hardware is suspended in a ‘poor man’s gyroscope’. The weight of all the components keeps the camera more or less upright all the time. The wobbliness of the camera gives the images some welcome dynamism, emphasising that you are indeed looking at footage from a rolling ball.

Anamorphic Puzzles

Throughout the project and actually still now, there is a tension between free and directed play. We were interested in giving people a shared bit of ludic public furniture. But we were also curious what kind of games could be played with this new plaything. In addition, we were very interested in taking over the area we would be playing in with some kind of visual markings.

One obvious starting point for a more structured playful activity to offer players was anamorphosis: “a distorted projection or perspective requiring the viewer to use special devices or occupy a specific vantage point to reconstitute the image.”

The Camparc balls would be streaming a donut-shaped video to an LED trailer in the middle of the play area. We thought it would be cool to create geometric drawings that would appear to float in the camera image.

As is often the case in our projects, we then needed to invent a process that would enable us to do this. In the end we managed to pull it off with an interesting assemblage of off-the-shelf software and hardware and lots of masking tape and patience.

We used an iPhone on a tripod with the same panoramic lens attached to it as we would be using inside of the balls. We made sure the lens was more or less at the same height as it would be in the ball. Using airplay we then streamed the camera view to a macbook and we used a simple app to overlay the image we would be drawing on top of the camera feed.

Then it was a matter of finding a nice spot to draw our anamorphic puzzle and masking it out (which involves lots of checking and rechecking between the drawing and the image on the macbook screen). At the game’s run on Strijp‑S we used spray chalk to fill in the shapes.

A shout-out to our friends at Pony Design Club who did an excellent job on all the visual materials for Camparc and who also painstakingly created the final set of anamorphic puzzles at Strijp‑S for the game’s event.

The end result looked very interesting and people enjoyed figuring out how to place the ball exactly so that the image kind of popped into view on the big screen.

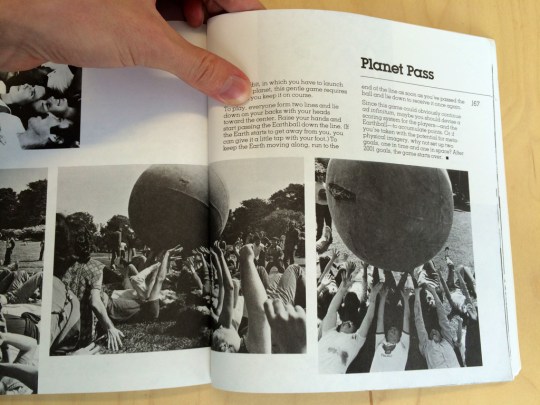

A Tribute to ‘Planet Pass’

I could not let the opportunity pass to stage a tribute to one of our sources of inspiration, the New Games movement. So in addition to free play with the ball and the anamorphic puzzles, we scheduled a few games of Planet Pass with the people in attendance.

It was a rather glorious experience. We also captured the footage from these sessions, a few clips of which made their way into the final video.

I found it very interesting to see how we managed to get an increasingly large group of people to join us just by starting to play the game and inviting people to help us out. The scale of the Camparc balls affords collaborative play so very easily. Outside of the Planet Pass sessions there were many occasions where people would spontaneously start to play together.

This is another quality of the project that I am rather fond of. Camparc is a playful technology which very elegantly lets people step into and out of playing alone or together.

Mark II

So that is the story of the making of Camparc. After this first version we were commissioned to improve on it. This second version, which we decided to name ‘Camparc Mark II’, was released as part of the STRP biennial. The most notable change is that we exchanged the large screen for a VR headset. Once again we encountered many challenges during the making-of. But that is a story for another day…

Making Camparc

This is a writeup of how we went about making Camparc, a panoramic camera ball.

The story starts in July 2014 when STRP asks us to make a public space game for a ‘scene’ — one of the events leading up to their 2015 biennial. They were looking for something eye-catching, accessible to a broad audience, fun for both participants and spectators, and of course it would need to be about tech in some way. The game would be played in the Strijp‑S area of Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

We cycled through a number of concepts together. An early idea was focused on doing things with large balls and maybe tracking them with cameras. A later concept was titled ‘Selfietopia’ and proposed a playground filled with camera toys for making selfies with.

Ingredients from those earlier concepts came together in Camparc: camera toys such as Panono and Bubl. New ways of seeing such as goal-line technology. The pleasure of playing with a huge ball in both Katamari Damacy and the earth ball games of the New Games movement.

It was our hope Camparc would let people playfully explore new ways of technologically augmented seeing, and that it would give people a tool with which to explore the Strijp‑S area in new ways.

Many different things had to come together in the final experience. For example, getting a video stream from the balls to show up on an LED trailer turned out to be non-trivial. But here I will talk about the design of the hardware and I will also go into how we created anamorphic puzzles for people to play with.

The Gilliam-Dyson Direction

So the starting point was to do something with big balls. We went on a hunt for a good base and eventually settled on water balls. They are large, transparent and afford opening and closing. Perfect for our purposes.

The notion of transparency and seeing the tech inside of the ball lead to a direction for the visual language which was equal parts Terry Gilliam sci-fi prop and James Dyson vacuum cleaner.

We worked with Aldo Hoeben on this project. He was responsible for the design and development of the balls as well as the software behind them. The cool thing about working with Aldo was that he has a background in industrial design, has an artistic practice focused on projection mapping and panoramic photography and is a 3D printing enthusiast to boot. In other words, his unique set of skills was a perfect match for the challenges of this project.

It was Aldo who starting from my Gilliam-Dyson direction created the brightly coloured custom 3D-printed parts which give Camparc its constructivist look. It is an aspect of the project I am still very proud of. More than once during a conversation with a player about ‘how it works’ was I able to simply point to every single component and talk them through it.

Another neat aspect of the balls is that all the hardware is suspended in a ‘poor man’s gyroscope’. The weight of all the components keeps the camera more or less upright all the time. The wobbliness of the camera gives the images some welcome dynamism, emphasising that you are indeed looking at footage from a rolling ball.

Anamorphic Puzzles

Throughout the project and actually still now, there is a tension between free and directed play. We were interested in giving people a shared bit of ludic public furniture. But we were also curious what kind of games could be played with this new plaything. In addition, we were very interested in taking over the area we would be playing in with some kind of visual markings.

One obvious starting point for a more structured playful activity to offer players was anamorphosis: “a distorted projection or perspective requiring the viewer to use special devices or occupy a specific vantage point to reconstitute the image.”

The Camparc balls would be streaming a donut-shaped video to an LED trailer in the middle of the play area. We thought it would be cool to create geometric drawings that would appear to float in the camera image.

As is often the case in our projects, we then needed to invent a process that would enable us to do this. In the end we managed to pull it off with an interesting assemblage of off-the-shelf software and hardware and lots of masking tape and patience.

We used an iPhone on a tripod with the same panoramic lens attached to it as we would be using inside of the balls. We made sure the lens was more or less at the same height as it would be in the ball. Using airplay we then streamed the camera view to a macbook and we used a simple app to overlay the image we would be drawing on top of the camera feed.

Then it was a matter of finding a nice spot to draw our anamorphic puzzle and masking it out (which involves lots of checking and rechecking between the drawing and the image on the macbook screen). At the game’s run on Strijp‑S we used spray chalk to fill in the shapes.

A shout-out to our friends at Pony Design Club who did an excellent job on all the visual materials for Camparc and who also painstakingly created the final set of anamorphic puzzles at Strijp‑S for the game’s event.

The end result looked very interesting and people enjoyed figuring out how to place the ball exactly so that the image kind of popped into view on the big screen.

A Tribute to ‘Planet Pass’

I could not let the opportunity pass to stage a tribute to one of our sources of inspiration, the New Games movement. So in addition to free play with the ball and the anamorphic puzzles, we scheduled a few games of Planet Pass with the people in attendance.

It was a rather glorious experience. We also captured the footage from these sessions, a few clips of which made their way into the final video.

I found it very interesting to see how we managed to get an increasingly large group of people to join us just by starting to play the game and inviting people to help us out. The scale of the Camparc balls affords collaborative play so very easily. Outside of the Planet Pass sessions there were many occasions where people would spontaneously start to play together.

This is another quality of the project that I am rather fond of. Camparc is a playful technology which very elegantly lets people step into and out of playing alone or together.

Mark II

So that is the story of the making of Camparc. After this first version we were commissioned to improve on it. This second version, which we decided to name ‘Camparc Mark II’, was released as part of the STRP biennial. The most notable change is that we exchanged the large screen for a VR headset. Once again we encountered many challenges during the making-of. But that is a story for another day…